General

Can NOTDEC avoid paying fees to CAF?

Answer

YES – for regular or big donations. (Otherwise, it's not worth the hassle. CAF fees are tiny for the time they save you and the work they save us!)

BUT, for regular giving and big one-off donations, please consider a simple alternative to "Donate" and CAF.

- Regular donations If you set up a regular donation in "Donate", NOTDEC UK will pay a fee to CAF every month. To avoid this, don't use "Donate": use Child Sponsorship. On the enquiry form there, choose "Other Monthly Donation". We'll then ask you to set up a Standing Order and, if appropriate, fill in a Gift Aid Declaration (on-line or by post). Hey presto! Monthly payments with NO fees to CAF.

- Large one-off donations (£2,000+) It's the same story. Give via "Donate", and CAF will get a tiny percentage of your cash. But a small percentage of a large sum is well worth saving. If you want NOTDEC to pay no CAF fee on your lump sum, again please use the Child Sponsorship form. There, choose "Other Monthly Donation"; and add a Message saying you want to make a large one-off donation of £X. If you wish, you can then fill in a Gift Aid Declaration (on-line or by post) and, finally, make a bank transfer or send us a cheque. Again, a big donation but no cut to CAF.

- Typical one-off donations CAF provides a very quick and efficient service at very low cost — including all the admin for reclaiming Gift Aid where relevant. The CAF fee could be avoided - though we might need to employ someone to do the admin. But, for standard single donations, it's simply not worth you or NOTDEC UK the effort involved! Instead, we can both say "thank heavens for CAF!" - and NOTDEC UK can continue to operate with no paid employees. Gift Aid your donation, and the extra tax we will reclaim on your behalf will dwarf CAF's fee - yet CAF will do all the donkey-work. The labourer is worthy of his – or her – hire!

When is an orphan NOT an orphan?

Answer

When it’s Ugandan!

A woman dies in childbirth. Her baby survives. If the child’s father is still alive, in the UK we wouldn’t call that child an “orphan”. There is still one natural parent living.

In most of the rest of the world, outside the priviledged West, it's different. In rural Uganda it’s certainly different.

What can the father do? He can’t earn his living and look after a toddler, let alone an unweaned baby. He can’t afford infant formula, which is both extortionate and in short supply, nor can he breastfeed the baby himself! So he can’t even feed his son or daughter. His only choice is to give the child up. In Uganda, the baby is an orphan. We can split hairs all we like about what the word "orphan" means, but help will be needed for some years – or the child’s life and health will hang by a thread.

That’s the world NOTDEC works in – with many sponsors supporting kids whose fathers are alive and kicking.

Or should we cling to our priviledge and split hairs?

Dorothy's personal profile?

Answer

Dorothy Nzirambi Komusana is NOTDEC Uganda's founder and a member of the management team. She still very much enjoys looking after babies and young children, and also devotes a lot of time to training house-mothers or helping with the routine day-to-day practicalities of running an orphanage.

Dorothy Nzirambi Komusana is NOTDEC Uganda's founder and a member of the management team. She still very much enjoys looking after babies and young children, and also devotes a lot of time to training house-mothers or helping with the routine day-to-day practicalities of running an orphanage.

Dorothy's schooling ended at Primary 6 (her father was ill and could not afford the fees); and, as a result, her written English is limited. This, coupled with her evident love of nursing babies, and her lower profile in the management team might lead some Europeans to underestimate her. This would be a serious mistake.

Particularly in difficult times, her strength of character stands out, and no-one can doubt her determination to fight for the children that God has put on her heart. In early 2015, for example, the orphanage was completely full and took the difficult decision to close to all new admissions until further notice. Despite this, people continued to arrive with babies they clearly could not feed or care for. Admitting the babies would open the floodgates — and they really couldn't cope with any more. But send them away, and memories of 2012 said that they would almost certainly die. What could be done?

Dorothy was decisive. To avoid creating precedents at Kabirizi, she decamped to premises in Kasese. There she offered short-term help and infant formula while families made their own arrangements, but — as in Ugandan hospitals — only if a family member stayed to look after the baby. Where appropriate, she also gave childcare training. This pragmatic approach has ensured that, so far, no babies have died and all are already being cared for by members of their wider family. [For more, see "Bottles & Basics" in The Baby Boom.]

Where there's a will ...

Is this a fair question?

Answer

Is this a fair answer?

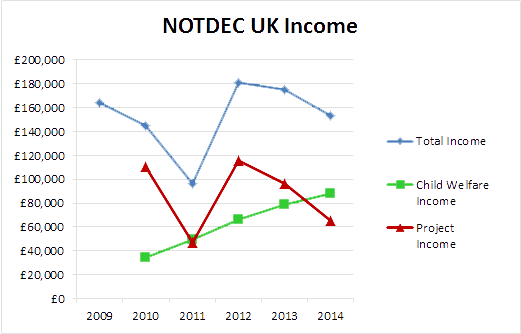

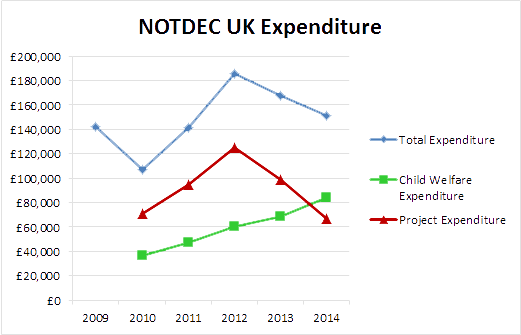

How have NOTDEC UK figures changed over the years?

Answer

Yes: a lot!

Yes: a lot!

Child Welfare Income is money given via child sponsorship or as lumps sums for the day-to-day needs of the children (food etc.) and all the routine running costs of the orphanage including staff. It does not cover building the orphanage, nor the capital cost of buying vehicles like the school bus and the tractor for hauling water, or computers for the orphanage office. All these and a whole host of other non-welfare costs are met out of Project Income — so called because the first task was to pay for the building project that produced the first four bungalows.

Project Income and Expenditure have bounced around considerably — reflecting particularly the various phases of construction at the orphanage — and have taken Total Income and Expenditure up and down with them. We do, however, accrue funds for maintenance and renewals.

By contrast, both Child Welfare Income and Expenditure were much more stable, though with a marked upward trend.

Total Income was low in 2011 because Project Income in that year was also down. That was because Project Income the previous year had greatly exceeded Project Expenditure, producing a very healthy surplus. However, Project Expenditure in 2011 substantially exceeded Project Income, and so quickly disposed of the surplus! NOTDEC does not ask for large sums for which it had no immediate need or for future unspecified projects.

| Financial Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Income | £164,050 | £144,965 | £96,276 | £181,505 | £175,347 | £153,370 | n/a |

| Child Welfare Income | n/a | £34,690 | £49,597 | £66,207 | £79,183 | £88,108 | n/a |

| Project Income | n/a | £110,275 | £46,679 | £115,298 | £96,164 | £65,062 | n/a |

| Travel Donations | n/a | £7,055 | £5,883 | £11,632 | £6,646 | £9,609 | n/a |

| Project Standing Orders | £4,348 | £8,088 | £8,048 | £3,444 | £7,945 | £7,560 | n/a |

| FInancial Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Expenditure | £142,612 | £107,193 | £141,732 | £185,573 | £167,480 | £151,435 | n/a |

| Child Welfare Expenditure | n/a | £36,469 | £47,010 | £60,700 | £68,650 | £84,165 | n/a |

| Project Expenditure | n/a | £70,724 | £94,722 | £124,873 | £98,830 | £67,270 | n/a |

| Bank Charges | n/a | £425 | £360 | £440 | £400 | £494 | n/a |

| Printing & Publicity | n/a | £866 | £0 | £674 | £140 | £13 | n/a |

| Travel | n/a | £7.055 | £5,883 | £11,632 | £6,646 | £9,609 | n/a |

| Equipment & Services | n/a | £13,478 | £7,564 | £6127 | £20,644 | £19,529 | n/a |

| Construction, Vehicles etc. | n/a | £48,900 | £80,915 | £106,000 | £71,000 | £37,625 | n/a |

Which school years are most likely to be repeated?

Answer

Based on data for the past five years, the table below looks at which school years are most likely to be repeated.

| Level | Years Analysed | Repeats | Percent | Index | Boys Index |

Girls Index |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 28 | 3 | 10.7% | 105 | 107 | 101 | |

| P2 | 25 | 1 | 4.0% | 39 | 60 | 0 | |

| P3 | 34 | 10 | 29.4% | 288 | 320 | 233 | |

| P4 | 27 | 4 | 14.8% | 145 | 64 | 253 | |

| P5 | 21 | 5 | 23.8% | 233 | 240 | 202 | |

| P6 | 21 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P7 | 21 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S1 | 17 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S2 | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S3 | 16 | 1 | 6.3% | 61 | 0 | 112 | |

| S4 | 10 | 1 | 10.0% | 98 | 0 | 144 | |

| S5 | 5 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S6 | 5 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Absent | 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| All | 245 | 25 | 10.2% | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Index values show how likely each school year was to be repeated - with index 100 representing the average rate.

Years scoring over 100 have above average repeat rates (200 = twice the average).

Years scoring under 100 have below average rates (50 = half the average).

Repeat rates are highest in P3-P5. Allowing for the small sample sizes, the pattern is the same for girls and boys.

There is a secondary peak in S3 & S4. So far, only girls have had to repeat these year — even though only slightly more girls than boys have reached that stage.

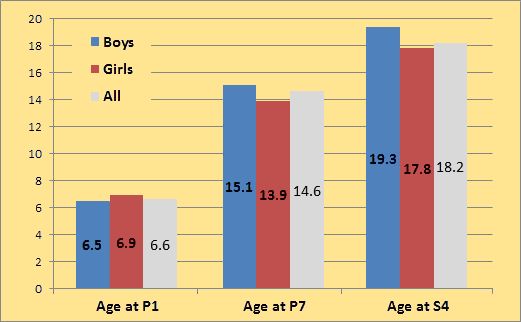

Do boys or girls progress faster?

Answer

The chart shows NOTDEC Uganda children's progress through school — focusing on Primary Education because far fewer have so far reached Secondary level.

Age by Key Stage and Gender

On average, boys enter Primary 1 at age 6.5 years — slightly earlier than the girls at 6.9. But, they don't maintain that lead — not reaching P7 until average age 15.1 compared with 13.9 for girls. By the end of Primary, therefore, the girls have a lead of something like 14 or 15 months.

And on into Secondary Education, the news for boys only gets worse. By S4, the girls' lead is 1.5 years or 18 months.

Caution Figures should be treated with care. The date of birth of most children is precisely known, but for others it is a guess — perhaps just a month and year, in a few cases only a year. Calculating averages from such data is rather risky. There is no reason to believe that this has distorted the results significantly, but it is impossible to be certain.

Note: longer bars mean slower progress!

Challenges?

Detailed question

What other challenges face NOTDEC in relation to education?

Answer

These pages focus on meeting each child's need to achieve a good and appropriate level education. There, the main challenges are about what we can do to help improve school performance — not just by providing the best possible start in the nursery, but by looking at motivation, careers advice and so on. We don't want kids who do better at school, but hate it. We want them to do better at school because that is what they want. This will always be a work in progress.

Longer term, we also face a number of major challenges, which may affect the kind of education and upbringing NOTDEC Uganda will be able to provide going forward:

- Resettling children with their wider families ("Repatriation") — removing many from local schools and NOTDEC Uganda's Christian teaching

- The rising cost of further and higher education — making it harder to send to University all NOTDEC Uganda children who could get there

- The shortage of jobs for qualified people - making children wonder why they should work hard at school if there aren't worthwhile jobs at the end of it all.

These issues are considered in more detail in Challenges: Education & Upbringing, where the question is set in the broader context of the kind of upbringing we aim to offer to the children in our care.

Local materials?

Detailed question

When building NOTDEC at Kabirizi, were local materials used?

Answer

Yes. Where possible we used locally-sourced materials, which strengthens the local economy.

It may also boost the job prospects of future NOTDEC teenagers, so we have to give it a go!

Bricks being made locally

The bricks here aren't the actual ones we used. Nice idea! But "just build it" conveys a greater sense of urgency.

Kasim making a door.

Kasim in nearby Kasese made the doors, door frames and windows. Who needs Everest?

Best money-saving design feature?

Answer

The best feature is undoubtedly the design of the houses, that keeps them cool without any artificial ventilation whatsoever. But you may already know about that from Getting it Right. And anyway, you could say it saved sweat and discomfort — not hard cash.

So, as best money saver, how about the windows — made a few miles away by Kasim in Kasese.

Building in Good Design

The windows we chose include an integral fire escape and have full height opening vents for good ventilation, making them ideal for the Ugandan climate.

The windows we chose include an integral fire escape and have full height opening vents for good ventilation, making them ideal for the Ugandan climate.

Air conditioning was out of the question, however, so that doesn't count as money-saved.

The money-saver was in finding windows with integral fire escapes, providing high safety standards without the cost of separate fire exits.And in buildings used by such large numbers of children, good provision of fire escapes is vitally important.