Secondary & Beyond

In the UK, surprisingly few kids from children's homes do well at school. At NOTDEC Uganda, some children struggle and have to repeat years even to complete Primary Education (P7), but things look slightly better. Though the bulk of children are still primary age or younger, NOTDEC Uganda now has 27 who have progressed to secondary level — including 12 who have finished their schooling — and several have reached Uni.

Opportunities Beyond Primary

After Primary (P7) comes Secondary, starting with S1 and ending at S4 (roughly equivalent to GCSE) or S6 for the more academic (think A-Levels with boarding, making it expensive). Then come follow-on vocational courses or — for those who're bright enough — perhaps college or University.

NOTDEC Uganda children who have finished their schooling so far have done vocational courses ranging from agriculture to midwifery or have gone to University. To date, six have reached University, including 5 women. NOTDEC Uganda has been able to fund University education thanks only to generous donations from supporters in Canada.

Girls Getting Ahead

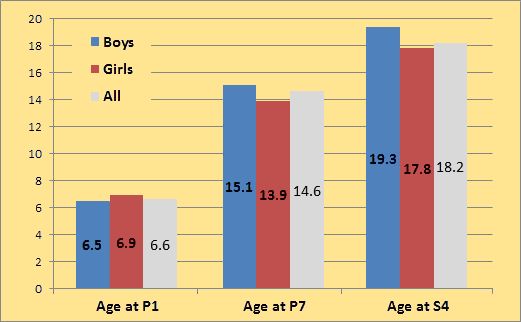

Note: longer bars mean slower progress!

On average, boys at NOTDEC Uganda reach Primary 1 at age 6.5 years — slightly earlier than the girls at age 6.9. But they don't maintain that lead. As a result of repeating years, they don't reach P7 until an average age of 15.1 years compared with 13.9 for girls.

On average, boys at NOTDEC Uganda reach Primary 1 at age 6.5 years — slightly earlier than the girls at age 6.9. But they don't maintain that lead. As a result of repeating years, they don't reach P7 until an average age of 15.1 years compared with 13.9 for girls.

And by S4, the girls' lead is 1.5 years.

Age by Key Stage and Gender

Boys Falling Behind

To try to understand the effect of repeating years, we analysed all children in school for 2+ consecutive years between 2010 and 2015. Of their 245 child years, 25 (or 10.2%) were repeats.

| Child Years Analysed* | Repeat Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | Percent | Index** | |

| Boys | 144 | 15 | 10.4% | 102 |

| Girls | 101 | 10 | 9.9% | 97 |

| Total | 245 | 25 | 10.2% | 100 |

*Repeating means staying at the same level in consecutive years. No child can be known to have repeated in their first data year, so that year is not counted in the years analysed!

** The average repeat rate across all children (10.2%) is set to an index score of 100. Using this yardstick, the repeat rate for boys is index 102, and that for the girls 97.

Both for girls and boys, the highest repeat rates were in P3-P5. But overall, it is boys who most often have to repeat a year. Repeats by boys were 10.4% of the years analysed compared with 9.9% for girls. Sample sizes are minute so we must not make too much of that tiny difference. However, only 3 children have repeated twice — and all are boys.

Finishing School

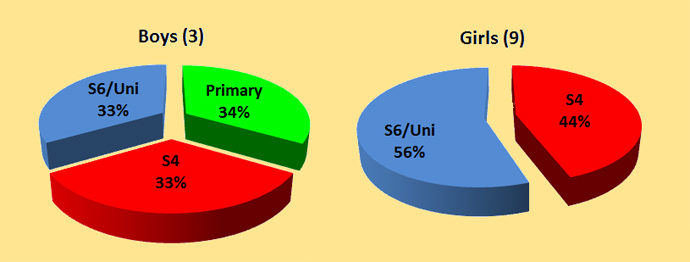

Final Education Level by Gender

Final Education Level by Gender

Only 12 NOTDEC Uganda children have finished school, so it's a bit early for a chart like this! Though the results "feel" right, with 9 girls and only 3 boys, they could be misleading. With such tiny numbers, individual ability and personal motivation might well be far more important than gender.

So far, however, girls have progressed faster and got much further than boys. Of our tiny sample, 5 girls are currently at University in Kampala – one in her final year of a Law degree. To date, only one boy has reached that level.

Why Might Girls Be Winning Out?

Girls repeat less, progress faster, get further than boys. Yet, entering P1, the boys were slightly ahead. If the change is real and not just random variations in our tiny samples, how might we explain it?

Could the answer lie in the different life paths open to men and women in rural SW Uganda? Though the economy is unsophisticated, a variety of jobs are open to young men at each educational level, so an inability or disinclination to study does not close all the options. For males, therefore, not bothering with study may not have a particularly serious downside — you'll just end up with a practical or manual job rather than anything needing exams.

For young women, things may look rather different. There are some higher-level jobs open to both sexes, and every reason why young women should compete hard for them. But at lower educational levels, opportunities are far fewer. In a very traditional society, many low skilled jobs are still "men's work". The big exception, of course, is having babies. For girls, a higher level of education then may be one way to guarantee yourself at least some choices. Otherwise you could end up like your house-mother! Though NOTDEC Uganda girls love their house-mothers, that may not be all that they want for themselves.

Is It Worth the Effort?

Will all this education pay-off — for NOTDEC Uganda, and for the children? Will there be jobs to match the degrees, or will well-qualified kids fail to find work which uses their skills? Initial signs are not wholly encouraging. The Ugandan Government needs to do more to develop the economy and so provide rewarding work for more young people.

Of course, we in Europe must also do all we can to help.